Full Paper (ArXiv) | Code (GitHub) | ELFW Dataset (Hippocratic Licence)

Rafael Redondo and Jaume Gibert

CC BY 2019-20

ELFW v2.0: it corrects face-to-label misalignments found in skin and hair-only LFW faces due to an entanglement between funneled and deep-funneled aligned faces in the first ELFW version. Although not planned experimental re-runs ahead, slightly higher overall accuracies and similar performance tendency regarding data augmentation are expected as compared to the related paper. Release date 23.02.2021.

Abstract

Existing face datasets often lack sufficient representation of occluding objects, which can hinder recognition, but also supply meaningful information to understand the visual context. In this work, we introduce Extended Labeled Faces in-the-Wild (ELFW), a dataset supplementing with additional face-related categories —and also additional faces— the originally released semantic labels in the vastly used Labeled Faces in-the-Wild (LFW) dataset. Additionally, two object-based data augmentation techniques are deployed to synthetically enrich under-represented categories which, in benchmarking experiments, reveal that not only segmenting the augmented categories improves, but also the remaining ones benefit.

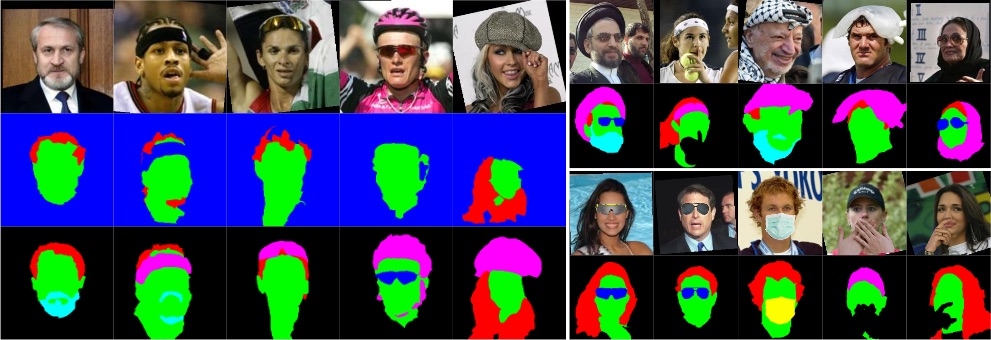

Examples of the ELFW dataset: the original LFW categories background, skin, and hair, the new categories beard-mustache, sunglasses, head-wearable, and the exclusively synthetic mouth-mask. (left) Re-labeled faces with manual refinement compared to the original LFW labels in blue background, (right-top) faces previously unlabeled in LFW, and (right-bottom) synthetic object augmentation with sunglasses, mouth-masks, and occluding hands.

Examples of the ELFW dataset: the original LFW categories background, skin, and hair, the new categories beard-mustache, sunglasses, head-wearable, and the exclusively synthetic mouth-mask. (left) Re-labeled faces with manual refinement compared to the original LFW labels in blue background, (right-top) faces previously unlabeled in LFW, and (right-bottom) synthetic object augmentation with sunglasses, mouth-masks, and occluding hands.

Purpose

The main goal of this work is to create a set of renewed labeled faces by improving the semantic description of objects commonly fluttering around faces in pictures, and thus enabling a richer context understanding in facial analysis applications. To this end, we extended the LFW dataset in three different ways:

- Updating the originally labeled semantic maps in LFW with new categories and refined contours.

- Manually annotating additional faces not originally labeled in LFW.

- Automatically superimposing synthetic objects to augment under-represented categories in order to improve their learning.

Extended Labeled Faces in-the-Wild

The Extended Label Faces in-the-Wild dataset (ELFW) builds upon the LFW dataset by keeping its three original categories (background, skin, and hair), extending them by relabeling cases with three additional new ones (beard-mustache, sunglasses, and head-wearable), and synthetically adding facial-related objects (sunglasses, hands, and mouth-mask).

Data Collection

From the 2,927 images annotated with the original categories (background, skin, and hair), a group of 596 was manually re-labeled from scratch because they contained at least one of the extending categories (beard-moustache, sunglasses, or head-wearable). Furthermore, from the remaining not labeled images with available superpixels —LFW was originally released with 5,749 superpixels maps—, 827 images having at least one of the extending categories were added up and labeled. In total, ELFW is made up of 3,754 labeled faces, where 1,423 have at least one of the new categories.

Data Augmentation

The category sunglasses is the worst balanced category throughout the collected data. Moreover, the dataset does not present even a single case of an image with a common object typically present in faces, mouth-masks. To this end, 40 diverse types of sunglasses and 12 diverse types of mouth masks were obtained from the Internet, manually retouched to guarantee an appropriate blending, and placed and resized proportionally to the interocular distance provided by the Viola-Jones face detector. A total of 2,003 faces were suitable for category augmentation. Blending source hands into faces requires realistic color and pose matching with respect to the targeted face.

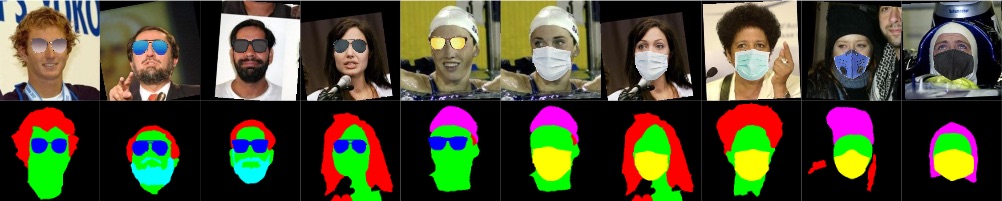

Examples of automatic category augmentation with sunglasses and mouth-mask in ELFW.

Examples of automatic category augmentation with sunglasses and mouth-mask in ELFW.

Hands are, by nature, one of the most frequent elements among occluders. However, they are an specially challenging object since the skin color shared with the face can entangle posterior face-hand discrimination. The hands used in this work were compiled from both Hand2Face and HandOverFace. Firstly, the source head pose —originally with hands on it— is matched against all the target head poses in ELFW by using Dlib. Secondly, the hands color is corrected according to each facial tone. The averaged color is transferred from the target face to the source hands by correcting the mean and standard deviation for each channel in the \(l\alpha\beta\) color space. The hands are placed and resized relative to both origin and destination face sizes.

Illustration of occluding hands synthetically attached to ELFW. The first and second rows (images and labels) show paired examples of re-used hands on different faces with their corresponding automatic color tone correction, scaling, and positioning. The third and fourth rows (images and labels) depict an assortment of hand poses, with the same automatic attachment procedure.

Illustration of occluding hands synthetically attached to ELFW. The first and second rows (images and labels) show paired examples of re-used hands on different faces with their corresponding automatic color tone correction, scaling, and positioning. The third and fourth rows (images and labels) depict an assortment of hand poses, with the same automatic attachment procedure.

Experiments: facial semantic segmentation

We chose two deep neural networks in the semantic segmentation state-of-the-art, a Fully Convolutional Network (FCN) and a much recent architecture such as DeepLabV3, which has been reported to perform remarkably well in several standard datasets.

Training hyper-parameters

Both models, FCN and DeepLabV3, used a COCO train2017 pre-trained ResNet-101 backbone, fine-tuned by minimizing a pixel-wise cross entropy loss under a \(16\) batch sized SGD optimizer, and by scheduling a multi-step learning rate to provoke an initial fast learning with \(10^{-3}\) at the very first epochs, latter lowered to \(2^{-4}\) at epoch \(35\), and finally \(0.4^{-5}\) at epoch \(90\), where the performance stabilized. Weight decay was set to \(5^{-4}\) and momentum to \(0.99\). In all experiments basic data augmentation such as random horizontal flips, affine shifts and image resize transformations were performed. An early-stop was set to \(30\) epochs without improving.

Augmentation factor

We defined \(\sigma\) to be the factor denoting the number of object-based augmentation faces added to the main non-augmented training dataset. For instance, \(\sigma=0.5\) means that an extra 50% with respect to the base train set (3,754) of synthetically augmented images have been added for training, i.e. 1,877 augmented images. When more than one augmentation asset is used, this factor is uniformly distributed among the different augmentation types.

Validation sets

To assess each of the augmented categories, separately and jointly, we used the same validation being careful with the nature of each data type. It was defined as 10% of the base train set, i.e. 376 images in total, where 62 out of 125 images wore real sunglasses and 28 out of 56 faces were originally occluded by real hands. The remaining halves were reserved for training. The validation set was then randomly populated with other faces from the remaining set.

Hardware and software

Each of the neural models was trained on an individual Nvidia GTX 1080Ti GPU. Regardless of the network architecture, the configuration with the smallest dataset \(\sigma=0\) required about 1 training day, while the largest one \(\sigma=1\) took about a week. We employed the frameworks PyTorch 1.1.0 and TorchVision 0.3.0 versions, which officially released implementations of both FCN and DeeplabV3 models with the ResNet-101 pre-trained backbones.

Validation Tests

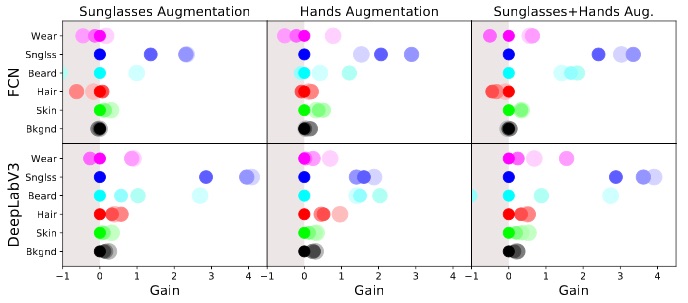

Overall, both augmentation techniques improve the segmentation accuracy for both networks, although not always steady. Indeed, \(\sigma=1\) tends to deliver the best results, i.e. the more augmentation data, generally the better. Although DeeplabV3 provides interesting multi-scale features, they probably do not make much of a difference in a dataset like this, since segments actually mostly preserve their size across images.

Gain effect per class on Mean IU with different data augmentation typesand ratios (\(\sigma\)) for both FCN and DeepLabV3 architectures. The size of each training dataset is proportionally represented by each circular area.

Field Experiments

We want to visualize the models’ generalization capacity on the mouth-mask category, which was purely synthetically added to the training set with \(\sigma = 0.5\). Head-wearables such as caps, wool hats or helmets were properly categorized, sunglasses were identified, and hair was acceptably segmented in a wide range of situations. The same sunglasses in the examples transited from sunglasses to head-wearable when moving from the eyes to the top of the head. The mouth-occluding objects were typically designated as mouth-mask. Furthermore, some failures simply happened spuriously, while others do have a direct link to the ELFW’s particularities. Hands occluding the mouth were sometimes confused with mouth-masks, specially when the nose was occluded too, which again does not frequently occur in the actual data augmentation strategy.

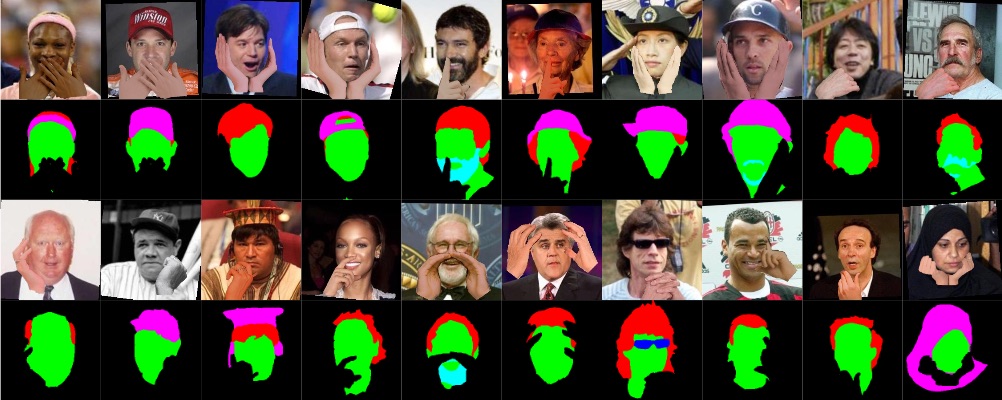

Labeling faces at the lab: sample assortment of successful detections of a casual variety of objects and poses never seen before by the neural network.

Labeling faces at the lab: mouth-masks detection. Even though mouth-mask only occurs synthetically in the train set, the segmentation network is able to generally give accurate results for such category.

Labeling faces at the lab: occluding with hands. Successful segmentation examples of hands occluding significant parts of the face.

Labeling faces at the lab: limitations due to severe head rotations, hands at unseen locations, and other category confusion.

Conclusions

The ELFW dataset has been presented as an extension of the widely used dataset LFW for semantic segmentation. It expands the set of images for which semantic ground-truth was available by labeling new images, defining new categories and correcting existing label maps. The main goal was to provide a broader contextual set of classes that are usually present around faces and may particularly harden identification and facial understanding in general. Different category augmentation strategies were deployed, which yielded better segmentation results on benchmarking deep models for the targeted classes, preserving and sometimes improving the performance for the remaining ones. In particular, we have also observed that the segmentation models were able to generalize to classes that were only seen synthetically at the training stage.

Acknowledgements

Authors want to thank Carles Bosch, Aniça Bukva, and Pedro Cavestany, who significantly contributed to annotate the ELFW dataset. Also to Umut Sayin for his accidental collaboration.